Lā Kūʻokoʻa

November 22, 2022 – Haylin Chock

Lā Kūʻokoʻa is celebrated every year on November 28. this day marked the anniversary in 1843 when England and France formally recognized the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi through the signing of the Anglo-Franco Proclamation and a verbal acknowledgment with the United States as a result of the efforts of emissaries Timoteo Haʻalilio, William Richards, and George Simpson. This independence day represents an affirmation of identity among the family of nations and pride in belonging to the lāhui of Hawaiʻi. It is a declaration of unwavering aloha ʻāina that continues to shine in our people for generations past, present, and future.

Anticipating further foreign encroachment on the Kingdom's territory following the Laplace Affair of 1839, King Kamehameha III sent a diplomatic delegation to the United States and across Europe to secure the recognition of Hawaiian independence. Timoteo Haʻalilio, William Richards, and Sir George Simpson were commissioned as joint Ministers Plenipotentiary on April 8, 1842, to act as diplomatic agents ranking below an ambassador but still possessing full power and authority to represent the Monarchy. Simpson was sent to Great Britain, while Haʻalilio and Richards went to the United States on July 8, 1842. The Hawaiian delegation secured the affirmation of United States President John Tyler of the Kingdomʻs recognized independence on December 19, 1842. Haʻalilio and Richards met Simpson in Europe to secure formal recognition from Great Britain and France. Their first meeting with the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs on February 22, 1843, with George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, was seen to be ineffective. First traveling to Brussels and then Paris, the Hawaiian delegation gained the support of King Leopold I of Belgium, who was sympathetic to the Hawaiian cause and promised to use his influence to help them gain recognition. On March 17, 1843, French foreign minister François Guizot, on behalf of King Louis Philippe I, assured the delegation that the French government would recognize Hawaiian independence. After returning to London, on April 1, 1843, Lord Aberdeen, on behalf of Queen Victoria, assured them, "Her Majesty's Government was willing and determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign."

During the time that this diplomatic delegation was away securing recognition of independence, a British naval captain Lord George Paulet, single-handedly occupied the Kingdom of Hawaii in the name of Queen Victoria without the authorization of his superiors. This event later came to be known as The Paulet affair. Lord George Paulet held the occupation for a five-months regardless of the protests of the Hawaiian government and people. Paulet collected and destroyed all Hawaiian national flags he could find. He then raised the British Union Flag, falsely claiming Hawaiʻi for England.

James F. B. Marshall, an American merchant of Ladd and Company, was invited aboard Boston, where he secretly met Hawaiian Kingdom minister Gerrit Parmele Judd. Judd gave Marshall an emergency commission as "envoy extraordinary" and sent him to plead the case for the liberation of the Hawaiian Kingdom in London. When Marshall arrived in Boston, he met with fellow Bostonians such as the U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster and future minister to Hawaii Henry A. Peirce on June 4, 1843. Webster gave him letters for Edward Everett, who was the American ambassador.

Thanks to the efforts of Marshall and the Hawaiian delegation, on July 26, Admiral Richard Darton Thomas sailed into Honolulu harbor on his flagship HMS Dublin. He requested an interview with King Kamehameha III. On July 31, with the arrival of American warships, Thomas informed Kamehameha III the occupation was over, and The Nation Of Hawaiʻi was recognized as neutral and independent. He reserved the right to protect British citizens but respected the Kingdom's and Monarchy's sovereignty. The site of a ceremony raising the flag of Hawaii was made into a park in downtown Honolulu, now named Thomas Square, in his honor. July 31 is celebrated as Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea or Restoration Day holiday. A phrase from the speech made by Kamehameha III became the motto of Hawaiʻi and is included on the coat of arms and Seal of Hawaii:

Ua Mau Ke Ea o ka ʻĀina I ka Pono, roughly translated into English as "The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness."

Later that year, on November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French governments formally recognized the independence of the Kingdom of Hawaii in the Anglo-Franco Proclamation, a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by Lord Aberdeen and the Comte de Saint-Aulaire, representatives of Queen Victoria and King Louis-Philippe, respectively. The United States declined to join in the proclamation stating that for such a recognition to be binding, it would require a formal treaty ratified by the United States Senate.

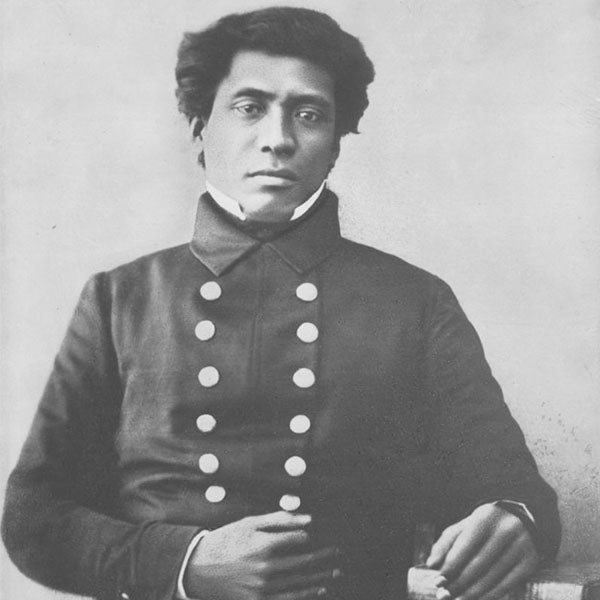

On this Day of Pride and recognition of our national identity, we leave you with an excerpt from Joseph Nawahī:

Ke Aloha Aina;

Heaha Ia?

“ O ke Aloha Aina, oia ka Ume Mageneti i loko o ka pu'uwai o ka Lahui, e kaohi ana i ka noho Kuokoa Lanakila ana o kona one hanau ponoi…Pela ke aloha i loko o ka pu'uwai o ke kanaka no kona aina hanau ponoi. Aole i ike maka ia ia mea he aloha, aole hoi hiki ke hoopaaia, aole hoi e hiki ke haha ia; aka, ua laha wale aku oia, a ua lele wale aku a pili i kona aina hanau ponoi iho, me he ume la o ke kui Mageneti.

Ina i hookokoke ia na kui hao Mageneti i kahi hookahi, alaila, he mea maopopo loa me ke kanalua ole o ka manao, ua ume like no lakou a pau loa kekahi i kekahi.

Pela hoi na lahui a me na kanaka a pau loa i noho pihaia e ka uhane aloha i ka aina hanau. E ike auanei ko lakou huki ana, ume ana, a me ko lakou kaohi ana i ka noho Kuokoa Lanakila ana o ko lakou aina hanau.

Na kela aloha iloko o lakou e lana, ua lilo ka hune, ka nele, ka inea a me na popilikia he nui i mea ole loa ia lakou. No ka mea, ua nui aku ke aloha no ka aina hanau mamua o na mea e ae a pau loa.

He holoholona ke kanaka ke nele oia i keia ano he Aloha Aina, a i ole ia, he kumakaia paha kona ano like loa. He haahaa loa ke kulana o ke kanaka aloha ole a kumakaia paha i kona one hanau. Aohe ona noonoo hou ia he pono ka i koe iaia, a e maalo ae ana oia iwaena o kona lahui ponoi iho me ka hoowahawaha loa ia aku e lakou.”

"That which we call Aloha' Āina is the magnetic pull in the heart of the patriot which compels the sovereign existence of the land of his birth. That is what the heart of a Hawaiian feels for his native land. His aloha cannot be seen, held, or felt, but it is widespread and points inevitably to the land of his ancestors, just like the needle of a compass.

Moreover, if many compasses are laid next to each other, we will see without doubt that every compass needle will be drawn to point in the same direction, [almost as if each encourages those around it to do so].

The same is true for all races and all people who are filled with love and loyalty for their ancestral lands. Eventually, they make known their undying support of, unity behind, and control over the independence of their ‘āina hānau.

It is that aloha within – that loyalty and love – that brings people hope; poverty, destitution, strife, and grief become as nothing to them because the love they hold for their birthland is greater than any other thing.

And as for the person who lacks the feelings and characteristics of Aloha ‘Āina, he is much like an animal or a turncoat. The status of such a man is low indeed, a man who has no aloha for his land or fails to act on its behalf. This man will cease to be thought of as having any kind of pono, and when he walks among his own people, he will be met only with scorn."

0 comments